It is not often that eclectic ancient artefacts of a region find their home in a structure that is equally impressive in its historic and creative value. This is what makes the architectural masterpiece of Kerala Folklore Museum so unique. Text and photographs by Gustasp & Jeroo Irani

It’s a relatively new building, just a few centuries old, that took seven and a half years to build. The elegant three-storey edifice of the Kerala Folklore Museum (keralafolkloremuseum.org) in Kochi has the bones and sinews of 25 antique structures that meld together to make a seamless cohesive whole.

The museum, with its attractive wood and laterite facade, is family-run and pops with colour, stocked as it is with over 6,000 artefacts of every age and stripe. The focus of the collection is on South India, particularly the coastal state of Kerala, and was amassed by a sole art dealer, the late George J Thaliath. This was a man driven by an overwhelming passion to unlock the mysteries of the past and save the state’s cultural heritage.

But the Kerala Folklore Museum is not a textbook history lesson. There is a sense of creative chaos here, artistic anarchy almost, of shifting colours, time, and space as though one is gazing through a kaleidoscope. When we visited the museum this February, it quickly became evident to us that for George and his wife Annie, the past was a giant jigsaw puzzle of carelessly discarded pieces of history that they tried to fit together as neatly as they could. And the museum was their playground.

While the treasures within are an eye-opener, the edifice, too, is a labour of love. A massive 700 cubic metres of wood, extracted from old crumbling homes, was restored and assembled by 62 skilled woodworkers. “We approached several architects but finally designed the building ourselves with the help of a structural engineer,” said Annie, whom we met while wandering the fragrant confines of the museum. (Annie now owns and runs the museum with the help of 16 staffers, and her son, 27-year-old Jacob.) It’s the only architectural museum in Kerala, claimed Annie, and the building embodies three styles—of Malabar, Cochin, and Travancore—typical of north, central, and south Kerala.

During his lifetime, George scoped the land for ancient temples, churches, and heritage homes that were in a state of disrepair. Annie shared his passion and often accompanied him on his travels. Over three decades, they bought and preserved artefacts, which they stored initially in their own home. The doors of the museum were thrown open on January 1, 2009, and the couple’s dream of sharing their treasures with the world finally saw fruition. Sadly, in November 2018, the 58-year-old George passed on.

Once we went past the imposing metal stambha (pillar) that rises in front of the museum, we wondered if we were in someone else’s nostalgic trance. The pillar had been rescued from a Lord Krishna temple located in the pilgrim town of Guruvayoor, and we caressed a wall that had inscriptions from the 16th century.

Leading up to the plinth were three stone steps, flanked by elephants, and worn smooth over the centuries by the footsteps of devotees. They had been rescued from a 16th-century temple in Tamil Nadu, while a 17th-century door frame with dwarapalakas (or guardian deities typical of temple entrances) welcomed us into the treasure trove.

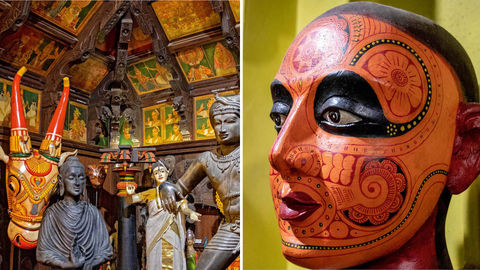

The wood-panelled interiors brimmed with finely carved antique ceilings and 150-year-old staircases with polished balustrades. A wide spectrum of art objects dazzled—an old carved temple door, the altar of a church, a 16th-century dome of a mosque, statues of Hindu deities, a painted ceiling, Kathakali and Theyyam dance masks, swords and shields, musical instruments, temple jewellery, silver artefacts, ornamental crosses from a Syrian church, statues of coquettish apsaras, murals, palkis for overweight kings, etc.

Slowly, a story emerged of a richly endowed state that in its prime had traded with the world. “We have Western, Islamic, Hindu, and Buddhist cultural influences in Kerala,” said the young Jacob. “Even Buddha, when he travelled to Sri Lanka, passed through Kerala.” For centuries, Kochi was a hub for the trade of spices, silk, ivory, porcelain, lacquered merchandise, and other luxury goods with China and the Arab world.

We climbed the steps up to the museum’s third storey, tingling with excitement. We had been told about the museum’s highlight, an 18th-century wooden ceiling, weighing 64 tonnes, with no support down the middle. Our necks swivelled upwards to gaze at the gorgeous expanse of carved wood, its weight supported by the lintels surrounding the hall. This third floor of the Kerala Folklore Museum is built like a dancing hall (or koothambalam in the local Malayalam language), a signature feature in the temples and palaces of yore. The museum’s koothambalam is enhanced by 253 modern murals and its foot-high stage thrums with the footwork of Bharatanatyam and Kathakali dancers when cultural performances are held. As was the case when Charles, Prince of Wales and heir apparent to the British throne, and his wife Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, stopped by in November 2013 to release a coffee-table book on the museum called Face.

At the end of the half-day tour, we were thoroughly bedazzled by the sheer scale of the exhibits and what they had revealed—the unbridled passion of one man for art and history. We returned to our boutique resort by the Kochi backwaters, Baymaas Lakehouse, to find our bearings in the present—cameos of a local casting a line in the pea-soup-green waters for some fish; the musical peal of church bells from the opposite bank; the sight of a red kayak cleaving the waters as we sat in a gazebo and sipped chilled coconut water and nibbled on crisp banana fritters. Gently, the backwaters flowed, with the certitude of centuries, carrying in their depths ancient stories waiting to be unravelled.

GETTING THERE

Most domestic airlines fly to Kochi International Airport from major cities in India.

STAY

In the Fort Kochi neighbourhood, vintage bungalows and warehouses have been converted into hotels. Xandari Harbour (xandari.com/harbour) is a delightful option; Brunton Boatyard (doubles from INR 8,000; cghearth.com) is charming as well. The city of Kochi has options like Grand Hyatt Kochi Bolgatty (doubles from INR 6,400; hyatt.com) and Radisson Blu Kochi (doubles from INR 3,800; radissonhotels.com). Baymaas Lakehouse (doubles from INR 5,533; natureresorts.in), located on the backwaters in Cheppanam, is a picturesque getaway.

RELATED: 5 Rare Places To Visit Near Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala